Today I’m excited to share a guest post by someone who has been instrumental in correcting several statistical errors in popular media reports regarding Pew’s 2013 report: The World’s Muslims: Religion, Politics, and Society. We’ll call this person Fred, and he’s currently the author of a new blog, Empethop.

Fred’s post below shows how one survey response from the report in particular—the percentage of Egyptian Muslims favoring death for apostasy—was widely misinterpreted and incorrectly cited by numerous writers in the wake of the controversial debate between Bill Maher, Sam Harris, and Ben Affleck on an October 2014 episode of Real Time.

I was one such author who lazily reported that Maher’s claim that “like 90%” of Egyptian Muslims favored death for apostasy was wrong, and that the actual figure was 64%. My source was Max Fisher’s 2013 article in the Washington Post. Fred, a reader of this site, brought it to my attention that Fisher had been wrong, and that the source Pew report cites 88%, not 64%. Fred’s efforts eventually led to the correction that you currently see in the Washington Post article.

The 64% figure, however, is still widely cited. I hope Fred’s article below helps explain why the error was made, how it spread, and why it’s so important to always check the original source. The version below is abridged, but you can read the full article at Fred’s blog (the unabridged version contains a much more thorough discussion of the statistics from the Pew report).

Most importantly, I want to thank Fred for his vigilance in pursuit of accuracy. Enjoy…

A Fact-Check of Bill Maher and His Critics: A Closer Look at Pew’s (2013) Survey Report

By Fred, via Empethop

January 2015

In an episode of HBO’s Real Time with Bill Maher, October 3, 2014, Maher and his guests engaged in a heated argument about the extent of fundamentalist beliefs among Muslims and the contention that many liberals are unwilling to criticize those beliefs. In the subsequent controversy, some journalists and other writers took up the important task of fact-checking the claims made in that now famous debate. One of the most often attempted corrections deals with Maher’s claim that a Pew study showed “like 90%” of Egyptian Muslims support death as a punishment for leaving Islam. Many who try to correct him allege that the correct Pew figure is 64%. This article fact-checks those claims and a few related ones by looking to the original Pew source documents, researchers, and data. I’ve documented this fact check in detail here.

The Pew Research Center survey report most often cited in this controversy is titled The World’s Muslims: Religion, Politics, and Society (April 30, 2013). In the Complete Report (April 30, 2013) and in the Topline Questionnaire, in a table on page 219 are shown the percentages of Muslims in each country listed, with each kind of response to Q92b, “Do you favor or oppose the following: the death penalty for people who leave the Muslim religion.” The table on p. 219 shows that 88% of Egyptian Muslims favored the death penalty for apostasy, 10% opposed it, and 1% didn’t know or else refused to answer. The table shows a wide range in support for the punishment, from about 1% in Kazakhstan to 88% in Egypt, with support in most countries below 50%. Note: I will be referring to the Complete Report throughout this article, so readers should keep it available for viewing.

Pew also published a brief article by Sahgal and Grim (July 2, 2013), highlighting some of the extreme restrictions on religion in Egypt. They wrote (parentheses are theirs): “Egyptian Muslims also back criminalizing apostasy, or leaving Islam for another religion. An overwhelming majority of Egyptian Muslims (88%), say converting away from Islam should be punishable by death.” A Pew study in 2010 found that 84% of Egyptian Muslims supported death for apostasy.

To provide verification that the data summaries on p. 219 are of the general samples of Muslims, I contacted the primary researcher of this (2013) study, who confirmed that 88% of Egyptian Muslims favored the death penalty for apostasy, and that the apostasy question was asked of all Muslims surveyed in the countries on p. 219. (Some contact information was removed at Dr. Bell’s request).

Pew made available to the public (June 4, 2014) the Data Set from which the percentages shown in the 2013 Complete Report were produced. Using freely-available statistical software, I’ve produced tables that will help clarify some issues about the numbers. In Table 3a, below, I show a cross-tabulation summarizing the percentages of the total, of Q79a (rows) by Q92b (columns) for Egyptian Muslims. (Following Pew’s instructions, I added the weight variable in the calculations). Q79a asked respondents whether they favored or opposed making sharia law the official law of the land in their country (see pp. 46 and 201, Complete Report). 74% supported sharia, and 86% of those who supported sharia favored the death penalty for apostasy (p. 55, Complete Report). Readers can compare the totals of the rows and columns in Table 3a with the rounded numbers for Egypt on pages 201 and 219, respectively, of the Complete Report to find that they do match up. Note that the “don’t know” and “refused” responses are merged in Pew’s report, but are separate in Pew’s data file.

In Egypt, less than 1% (.86%) overall opposed both official sharia and death for apostasy, while about 64% (63.80%) of Egyptian Muslims overall favored both. Note that the percentage for that latter response combination should not be confused with the percentage of Egyptian Muslims overall who favored the death penalty for apostasy (88.46%). Unfortunately, that confusion was made in a widely-cited secondary source.

A Major Source of the Error

That influential secondary source was a Washington Post article by Max Fisher (May 1, 2013) originally titled “64 percent of Muslims in Egypt and Pakistan support the death penalty for leaving Islam.” In the original uncorrected version (May 1, 2013), Fisher wrote:

“Although Pew [April 30, 2013] does not provide direct statistics for the share of Muslim respondents who support executing Muslims who convert to another religion, it does indicate the share of Muslims who support sharia and the share of these pro-sharia Muslims who back this policy. I’ve used this to extrapolate the data charted at the top of this page…”

By his own account, Fisher acted on the beliefs that Pew didn’t provide the statistics for the overall samples, and that he could extrapolate them from the limited information that he did have. Apparently, he overlooked or didn’t read adequately the report materials, available from the opening page, which do provide the statistics for the overall samples. For each country that he included in his calculations, he apparently multiplied the proportion supporting sharia (e.g., for Egypt, .74) by the proportion of sharia-supporters favoring death for apostasy (.86 for Egypt) to get what he described as the percentage of Muslims who supported the death penalty for apostasy (for Egypt, about 64%, or 63.64% based on multiplying the rounded numbers). As can be seen from the cross-tabulation of the data for Egypt in Table 3a, he obtained (a rough estimate of) the percentage of Egyptian Muslims who favored both official sharia and death for apostasy, not the overall percentage who favored death for apostasy.

Fisher presented his numbers for most of the countries in a red bar plot erroneously titled “Share of Muslims who support the death penalty for leaving Islam.” In the text of the original article, he referred to his numbers as “Pew’s data”:

“According to Pew’s data, 78 percent of Afghan Muslims say they support laws condemning to death anyone who gives up Islam. In both Egypt and Pakistan, 64 percent report holding this view. This is also the majority view among Muslims in Malaysia, Jordan and the Palestinian territories.”

On p. 219 of Pew’s (2013) Complete Report, the table shows that 79% of Muslims in Afghanistan and 75% of Muslims in Pakistan favored death for apostasy.

On October 15 (2014), I emailed the Washington Post, notifying them of the erroneous apostasy numbers in Fisher’s May 1, 2013 article (and in another article by him, dated May 2, 2013), providing them with a link to the Complete Report, and citing page 219. On about October 28 or 29, they made a partial correction to Fisher’s May 1, 2013 article, changing the title and stating in the text that 88% of Egyptian Muslims favored the death penalty for apostasy. However, the corrected article contained other errors, including a new error stating that 62% of Pakistani Muslims favored the death penalty for apostasy. (For a summary of my attempts to get various sources to correct their numbers, see Appendix III in my detailed article).

Some sources reported Pew’s (2013) apostasy numbers correctly. I haven’t done a thorough search, but here is a brief, casual, non-scientific sample of people who got the apostasy numbers right: Eugene Volokh (May 2, 2013); Andrew Bostom (May 4, 2013); Shadi Hamid (2014); and Nicholas Kristof (October 8, 2014).

Many people from multiple sides of the debate over Maher’s comments made or relayed the 64% error, and many cited Fisher’s (May 1, 2013) Washington Post article as though it were a valid presentation of the Pew (April 30, 2013) results [see Appendix IV in my detailed article]. Many writers went further, relying on Fisher’s article in attempting to correct Maher’s “90%” claim [see Appendix IV in my detailed article]. Here is a typical attempt, in this case by Dean Obeidallah at CNN Opinion (October 7, 2014):

“Maher then cited a Pew Research poll that he claimed found that 90% of Egyptians supported the death penalty for those who left Islam. I’m not sure where Maher got his numbers, but a 2013 Pew poll actually found only 64% of Egyptians supported this — still alarmingly high, but not 90%…”

He mentions the Pew (2013) study but links to the May 1, 2013 Washington Post article. Obeidallah’s article remains uncorrected (as of February 8, 2015), though he apparently ignored a correspondent’s attempt to correct him on twitter on October 9th and 17th, 2014.

Aslan Spreads the Error, Adds More Errors

In the debate in the weeks following Maher’s comments, Reza Aslan appeared often in the popular media. In an interview on “All In with Chris Hayes” (October 13, 2014), Aslan apparently accepted the same false assumption used in the original Fisher (May 1, 2013) article, as shown in the exchange below on MSNBC (The relevant part of the video clip begins at about 2:50):

Chris Hayes: I want to cite this poll that Bill Maher and Sam Harris, who is an atheist author who was on Bill Maher, who sort of have, have built a lot of this around. This is a Pew Research poll. I think it was conducted in 2013 of different views. This is views of Egyptian Muslims: 74% of Egyptian Muslims say sharia should be official law—that is, of course, sort of Qur’anically-derived religious law—and 86% of those say that there should be a death penalty for converts, for people who leave Islam. Now, that’s about 60% of folks when you multiply those two—64% that—when you multiply those two together. Now, that’s a troubling polling result, I think both you and I would agree, right?

Reza Aslan: The second number is a troubling poll result. The first one, you have to understand that those very same, that very same poll showed that of that 70-something percent, there was a massive diversity of views of what they even meant by sharia. We’re talking about marriage and divorce laws, and inheritance laws, as well as penal laws. But you’re right. 64% wanting the death penalty for, for converts out of Islam is incredibly frightening, until you read the rest of the poll wherein 75% of Egyptians also wanted religious freedom. If that sounds like a contradiction, it is, because religion and religious-lived experience is full of contradictions. So, 64% wanting the death penalty, that’s scary. But, of course, in neighboring Tunisia, it’s about 12%. In, let’s say Lebanon, it’s 1 in 6. In Turkey, it’s 5%.”

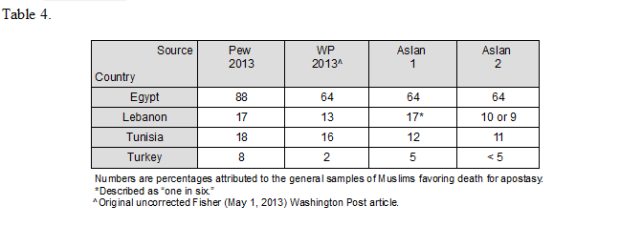

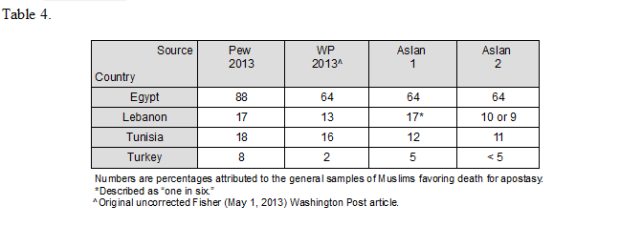

Hayes’ multiplying of the two percentages to get 64% is consistent with Fisher’s extrapolation; Pew didn’t do that in their report. Aslan strongly implies, to the naïve viewer, that he’s read from the same Pew (April 30, 2013) report, particularly when he says “that very same poll showed that…” and “until you read the rest of the poll, wherein…” In addition to Aslan’s 64% error for Egypt, page 219 of the Complete Report shows that his 12% for Tunisia and 5% for Turkey are incorrect; Pew’s figures are 18% and 8%, respectively. His errors for Tunisia and Turkey are not large. What’s more significant about them—together with his 64% error which is quite large—is that they suggest that he is unaware of p. 219 of the Complete Report (or Topline Questionnaire). (I deal with his claim of “75%” support for “religious freedom” in the next section, below)

Aslan’s approximation for Lebanon, phrased as “one in six,” happens to be consistent with the 17% on p. 219 of the Complete Report, though “one-in-six” is not uniquely linked to 17%. In a later interview with Hartmann, discussed below, Aslan describes the figure for Lebanon incorrectly as “10 or 9%,” which supports the idea that he hadn’t read p. 219.

Aslan also spread the 64% error via Twitter: “64% of Egyptians favor death for apostasy. 75% of Egyptians favor full religious freedoms. That contradiction sums up how religion is LIVED.” (October 13, 2014). When the author of Uncertainty Blog challenged Aslan’s 64% figure, Aslan tried to correct him, replying “@uncertaintyblog nope. 64%,” and adding a link to the original Fisher (May 1, 2013) Washington Post article. Aslan had also spread the error via AslanMedia (Facebook, October 11, 2014), citing another Washington Post article that, at that time, contained an erroneous presentation of Pew’s (2013) apostasy and adultery numbers.

Aslan revisited the apostasy numbers in an interview with host Thom Hartmann (October 20, 2014) on the program “Conversations With Great Minds,” shown on Russia Today (RT). The relevant section in Part 1, below, starts at about 3:00 into the linked video [my brackets]:

Hartmann: “When people like Sam Harris [and Bill Maher], for example, attack Islam, they often point to last year’s Pew study of the Islamic world. From the Western point of view, that study showed some pretty shocking stuff, like how 86% of Egyptians, and 76% of Pakistanis, support the death penalty for [struggles with the word] apostasy—am I, I always mangle that word but—”

Aslan: “For apostasy, yeah.”

Hartmann: “Apostasy. Thank you. How should we interpret this study and others like it?”

Aslan: “Well, first of all, those numbers are incorrect. It’s actually 64% of Egyptians who support the death penalty for apostasy, which is outrageously high. But it’s also not very instructive, either about Egypt or about the larger Muslim world. For instance, in neighboring Tunisia, the number is like 11%. In Lebanon, it’s about 10 or 9%, I believe. In Turkey I th— it’s less than 5%. So what some Egyptians believe is not instructive of the larger Muslim world. But it’s even more complicated than that, because the exact same poll that showed that 64% of Egyptians favored the death penalty for apostasy from Islam, also indicated that 75% of Egyptians want full religious freedoms for all Egyptians in the country. And if that sounds like a contradiction, that’s because it is a contradiction.”

Hartmann evidently didn’t have the appropriate data prepared, and did not question Aslan about his numbers. Aslan conveys firm confidence about the numbers, matter-of-factly “correcting” Hartmann with the 64% figure, and talking about the complication of the religious freedom result that appears to contradict the apostasy result. Again, he gives the impression, to the naïve viewer, of someone who has read the Pew survey. Note the downward migration of Aslan’s numbers for Tunisia and Lebanon, and the change in phrasing for Turkey, since his interview with Chris Hayes. I’ve summarized in Table 4 the relevant Pew (April 30, 2013) and Washington Post (May 1, 2013) numbers for comparison with the various numbers Aslan mentioned in the two interviews.

Do 75% of Egyptian Muslims Support Religious Freedom?

In his Washington Post (May 1, 2013) article, Fisher wrote:

“…majorities of Muslims in the countries surveyed, sometimes vast majorities, said they support religious freedom. That includes, for example, more than 75 percent of Egyptians and more than 95 percent of Pakistanis. It might seem like a glaring contradiction. And it is a contradiction…”

Like the 64% figure for the apostasy question, the figure of 75% (or the phrase “more than 75%”) support among Egyptian Muslims overall for religious freedom is not mentioned in the Pew (2013) report. Note that Aslan’s talking points from the Hayes and Hartmann interviews about the 64% apostasy figure and the 75% figure for religious freedom that “sounds like a contradiction…is a contradiction…” seem to come from Fisher’s article.

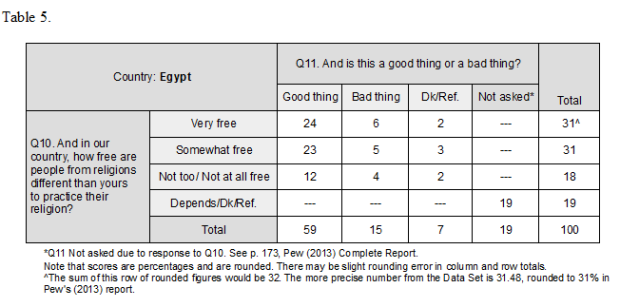

For its measure of Muslims’ support for the religious freedom of non-Muslims, Pew uses responses from two questions, Q10 and Q11, where the latter is a follow-up to the former. Here are the questions:

Q10: “And in our country, how free are people from religions different than yours to practice their religion? Are they very free to practice their religion, somewhat free, not too free, or not at all free to practice their religion?”

Q11: “…And is this a good thing or a bad thing?”

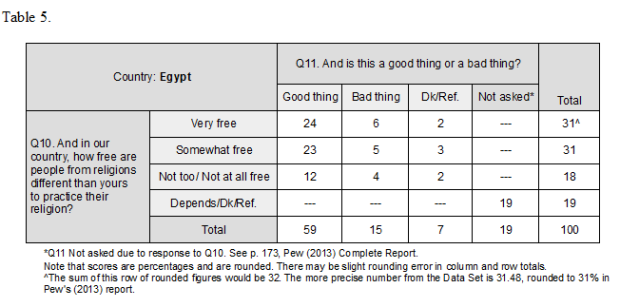

If a respondent answered “very free” to Q10, and said that that was “a good thing” in response to Q11, Pew deemed that pair of responses to indicate support for the religious freedom of non-Muslims. On pp. 63 and 172 (Complete Report), Pew shows data for Muslims who said, in response to Q10, that non-Muslims were “very free” to practice their (non-Muslim) faith in their country (e.g., Egypt). That subset is 31% of Egyptian Muslims overall, as Pew indicates on pages 62, 63, and 172 of the Complete Report. Of that 31% of Egyptian Muslims, 77% said that non-Muslims being very free to practice their faith was a “good thing” (p. 63). 77% of the 31% subset is 24% of Egyptian Muslims overall. The table for Q11 on p. 173 shows that 24% of Egyptian Muslims overall said non-Muslims were very free and that that was a good thing. (I summarize those results for Egypt in cross-tabulated format in Table 5, below). In other words, applying Pew’s own measure of Muslims’ support for the religious freedom of non-Muslims, we find that only 24% of Egyptian Muslims overall support it. Fisher appears to have taken the 77% of the subset as “more than 75 percent” of Egyptian Muslims overall. His “95 percent” claim for Pakistan also involves the same kind of error. Aslan reported the same error as did Fisher for Egypt, possibly due to having misread or not having read the original report, or due to having relied on Fisher’s article.

Summary

According to Pew (April 30, 2013), 88% of Egyptian Muslims support the death penalty for people who leave Islam (p. 219, Complete Report). That happens to be close to what Maher claimed. His critics who claimed that the Pew figure in question was 64% were in many cases relying on an erroneous secondary source from the popular media instead of reading the original Pew source with due diligence. Those who claimed that 75% (or more) of Egyptian Muslims supported religious freedom seem to have not read (or to have misread) the Pew (2013) report, which indicates that 24% of Egyptian Muslims overall supported “religious freedom” for non-Muslims (p. 173, Complete Report). This article highlights the perils of relying too heavily on secondary sources, and the need for due diligence in evaluating claims.

Read the full article here.